This is one of a short series of posts about Epiphany themes in early Christian papyri.

This one is long, so we’re just going to jump right in.

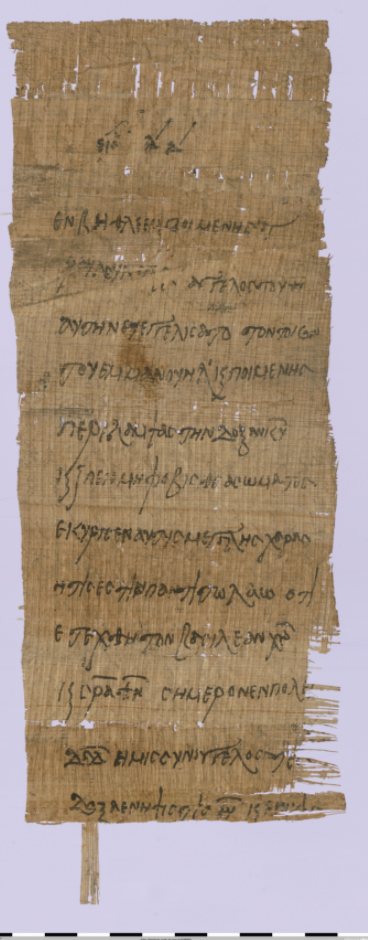

P.Berol. 11633

Description

Hymne über die Taufe Christi im Jordan durch Johannes, die innerhalb des liturgischen Jahres zum Theophaneia-Fest (Epiphanias) am 6. Januar gehört. 5. – 6. Jh. n.Chr.

P.Berol. 11633 (TM 64689), dated to ad 400–599, is called a “Theophany Hymn” by the editor of its editio princeps.[1] The papyrus focuses on events traditionally associated with the epiphany of Jesus.[2] It is a single sheet, 12cm wide and over 32cm long, with writing only on the recto. Nomina sacra and other abbreviations are used in the papyrus. Three primary sections are marked in the text by use of ekthesis at the start of a section. In some cases colons and tildes (lines 28 and 44) are used to fill remaining line space at the end of a section. Slashes (“/”) are used throughout to mark units.

Contents

Epiphany is a feast of the church (January 6) that was originally associated with the baptism of Jesus. While the feast originated in the eastern church and also included themes of the nativity, the western church began celebrating it in association with the miracle at the wedding in Cana.[3] The word “epiphany” has ties to the Greek word that means “to reveal,” so epiphany is about the revelation of Christ to the world. This revealing could be understood as his nativity, or as his baptism by John marking the beginning of his ministry, or as the miracle at the wedding in Cana indicating his first recorded miracle.

This liturgical papyrus mentions all these events as well as others from the life of Jesus as recorded in the gospels. At least one line from the first part is missing, but the available text begins with rejoicing “in the holy pool,” a reference to a baptismal font.[4] References to the glory and power of the Lord function as allusions to Luke 1:35 and 2:9 to end the first part.

The second part begins by echoing the Psalms (100:1 [lxx 99:1]; 66:1 [lxx 65:1]; 98:4 [lxx 97:4]) with a call to the whole earth to shout aloud to the Lord. This call to worship is followed by a call to rejoice (perhaps echoing Ps 96:4b [lxx 97:4b]) and a call to “meet the bridegroom” in Bethlehem (referencing Jesus’ birth) who also performed the miracle at Cana changing water into wine (Jn 2:1–11), who also healed the blind man at Siloam (Jn 9:1–12), who cleansed the leper by simply speaking (possibly Mt 8:1–4 || Mk 1:40–45; Lk 5:12–16), and who used five loaves to feed five thousand (Mt 14:13–31 || Mk 6:32–34; Lk 9:10–17; Jn 6:1–15). The balance of the second part sets the scene of Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan. Jesus’ title of “the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn 1:29) is echoed, John the Baptist is referred to as “the forerunner,” and the response of God the Father to Jesus’ baptism, “This is my beloved son, in whom I am well-pleased” (Mt 3:17) ends the section.

Part three returns to the baptism of Jesus, providing what amounts to an intimate overhearing of what seems framed as a whispered conversation between Jesus and John immediately before the baptism. After the baptism, the mountains and hills rejoice, and the words of the Father are extended with an additional command: “This is my beloved son, in whom I am well-pleased. Fear him.”

Translation[5]

Part I

(1) And he rejoiced upon the (2) holy pool

For in the midst of the (3) earth and heaven (4) confessing the Christ

and (5) treating the enemies arrogantly …

For the glory (6) of the Lord encircled him

(7) and his power will overshadow you.

Part II

(8) Shout aloud to the Lord all the earth

(9) because he appeared upon the earth, who was God before the (10) ages, the Word.

(11) Come, let us rejoice exceedingly and let (12) us celebrate!

Come, let us (13) meet the bridegroom, the one in (14) Bethlehem,

the one who with the Father (15) and the Holy Spirit

who was invited (16) to the wedding as a man and the (17) water was changed into wine;

who (18) gave sight to the blind one in Siloam;

(19) who cleansed the leper by his word.

(20) From five loaves (21) into five thousands were satisfied

(22) He went into the water of the Jordan,

(23) the lamb of God who takes away the (24) sin of the world,

to be baptized (25) by the forerunner.

(26) And the voice from the Father saying,

(27) “This one is my beloved (28) Son in whom I am well pleased.”~

Part III

(29) We were filled with great joy (30) upon seeing the Jordan

(31) when the one born upon earth as a man (32–34) appeared in it

and the forerunner himself listened to your voice saying,

“Let us (35) complete the plans of the Father.”

(36) “Like the Lord wanted,” (37) said John

You, Christ, came down (38) into the water,

The mountains leaped (39) like rams

and the hills like a lamb (40) of the sheep.

As you arose (41) from the Jordan

a voice has (42) come from the sky to you

(43) “This one is my beloved (44) Son in whom I am well pleased.

(45) Fear him.”~

Discussion

Visual indicators (ekthesis and sometimes extended tildes) mark the start or end of three sections on this 32-centimeter-long papyrus. The first part (lines 1–7) is missing at least a portion from its beginning, but the available material alludes to passages in the Psalms and in Luke.

The first available line mentions “rejoicing” using the same terminology found in Luke 1:47 and Ps. 35:9 [lxx 34:9] that speaks of rejoicing in the Lord. Here, however, the focus is on rejoicing for the baptismal font (“holy pool”) due to the epiphany emphasis on the baptism of Christ. The next lines (2–4) testify that Christ is being confessed from the midst of earth and heaven; this is followed by further allusion to Lucan nativity passages (lines 5–6 to Luke 2:9; line 7 to Luke 1:35).

The second part (lines 8–28) begins with phrasing common to the Psalms: “Shout aloud to the Lord all the earth!” (cf. Ps 100:1 [lxx 99:1]; 66:1 [lxx 65:1]; 98:4 [lxx 97:4]), providing the reason for shouting (perhaps in praise): “because he (Jesus) appeared upon the earth.” The next line provides information to reconcile the “he” with Jesus. It describes him as the one “who was God before the ages” and then further appositionally associates him with the term used to represent Jesus in John 1:1, the word. Again, there is rejoicing and celebration at this arrival. The nativity is directly referenced with mention of “Bethlehem” (13–14), even though the one in Bethlehem is equated with “the bridegroom.”

The frame of reference moves from the nativity (the earthly arrival and manifestation of the Messiah) to the wedding in Cana (the first recorded miracle of Christ in the gospels, a public manifestation of the Messiah). The entire Trinity is posited to be where “the water was changed into wine” (14–17). From here more miracles from the early ministry of Jesus are mentioned. Regarding Epiphany and early miracles of Jesus, Martinez notes:

Miracle narratives, especially those that Jesus performed early in his career, are always appropriate in an epiphanal context, since they, like his birth and baptism, manifest his true nature. We should however note, that the roster of miracles in this section is not randomly selected. In fact, three that are here listed have distinct ties to the celebration of Epiphany in various traditions.[6]

The miracles referenced include the healing of the blind man at Siloam (17–19, John 9), the healing of a leper (19–20, Mt 8:1–4 || Mk 1:40–45; Lk 5:12–16), and the feeding of the 5,000 (20–21, Mt 14:13–31 || Mk 6:32–34; Lk 9:10–17; Jn 6:1–15). Each of these miracles, as Martinez notes, has been tied to Epiphany in one way or another, and each of them contribute to the increasing expectation of the mention of the baptism of Jesus, the other central event tied to Epiphany. It has been foreshadowed with “bridegroom” language (13) and was explicitly alluded to by listing the changing of water into wine as the first miracle (15–16) in the miracle list.

The transition into the account of Jesus’ baptism is introduced by simply placing Jesus in the water of the Jordan river (22–23), directly referencing to the account of Jesus’ baptism (Mk 1:9–11 || Mt 3:13–17; Lk 3:21–22) and then borrowing phrasing from Jn 1:29, “The lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (lines 23–24). The effect is to identify the “lamb of God” as the subject who went into the water, skilfully placing Jesus as identified in John’s gospel – which does not directly mention John baptizing Jesus (Jn 1:19–34) – as the subject of synoptic gospels’ account of Jesus’ baptism.

The purpose of Jesus’ entering the Jordan river was “to be baptized by the forerunner” (lines 24–25). The “forerunner,” also mentioned in line 34, is a reference to John the Baptist. This language styles John as one who goes before Jesus, calling out attention to him to announce his arrival (cf. Is 40:3–11; Mal 3:1).[7] Jesus here is referred to as “the one born upon earth as a man” (30–31), testifying to the human nature of Jesus and implying at the same time that he is more than human.

After this is perhaps the most normal, human portion of the entire liturgy. Before the baptism of Jesus happens, John and Jesus have a brief conversation. The words “Let us complete the plans of the Father” are put in the mouth of Jesus, with an immediate response from John of “Like the Lord wanted” (34–37). The moment reads almost as a whispered conversation between the two primary participants immediately prior to the actual act of baptism. In the context of the liturgy, the conversation also confirms that John the Baptist and Jesus knew exactly what they were doing and knew the impact of the baptism. Unlike the canonical accounts of Jesus’ baptism which record John’s protestations about not being worthy (Mt 3:14–15), this account paints John as in tune with the will of God and willing to perform the baptism without hesitation.

This account of Jesus’ baptism is framed in a liturgy as a group recollection of the baptism event. The response of the group to the baptism is testimony of the earth and the animals upon it rejoicing as Jesus descends into the water. The rejoicing is affirmed as Jesus rises out of the water again with a repetition and expansion of lines 27–28 as audible testimony from the Father: “This is my beloved son in whom I am well pleased. Fear him” (cf. Mk 1:11 || Mt 3:17; Lk 3:22).

Bibliography

Cross, F. L., and E. A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. 3rd Revised. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Friedman, David Noel, ed. The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary. 6 vols. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1992.

Martinez, David G. “Epiphany Themes in Christian Liturgies on Papyrus.” Pages 187–215 in Light from the East. Papyrologische Kommentare Zum Neuen Testament. Edited by Peter Artz-Grabner and Christina Kreinecker. Vol. 39 of Philippika. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2010.

Treu, Kurt. “Neue Berliner Liturgische Papyri.” AfP 21 (1971): 57–82.

[1] Kurt Treu, “Neue Berliner Liturgische Papyri,” AfP 21 (1971): 62–67.

[2] David G. Martinez, “Epiphany Themes in Christian Liturgies on Papyrus,” in Light from the East. Papyrologische Kommentare Zum Neuen Testament, ed. Peter Artz-Grabner and Christina Kreinecker, vol. 39 of Philippika (Harrassowitz Verlag, 2010), 198–199.

[3] F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd Revised. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 557.

[4] Martinez, “Epiphany Themes in Christian Liturgies on Papyrus,” 198.

[5] Treu, “Neue Berliner Liturgische Papyri,” 64–65.

[6] Martinez, “Epiphany Themes in Christian Liturgies on Papyrus,” 198–99.

[7] David Noel Friedman, ed., The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, 6 vols. (New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1992), 2:830.

If you’ve celebrated Easter as a Christian, you’re familiar with the story as it is presented in the canonical gospels.

If you’ve celebrated Easter as a Christian, you’re familiar with the story as it is presented in the canonical gospels.